Oil Painting Info

Edward Hopper: Capturing Urban Solitude with Light and Shadow

Edward Hopper (1882-1967), a master of American realism, was born in Nyack, New York, into a middle-class family. His early love for painting was nurtured by his mother, a passionate art enthusiast, while his solitary nature, shaped by childhood experiences of bullying, allowed him to observe the unnoticed details of everyday life. This keen eye for the subtle and unspoken later became the hallmark of his work, immortalizing urban loneliness through his extraordinary interplay of light and shadow.

Even at the age of nine, Hopper’s talent for conveying emotions through imagery was evident. In his early piece, Little Boy Looking at the Sea (1891), the lone figure of a boy stands quietly before the ocean, hands clasped behind him, his head slightly bowed. This haunting scene encapsulates a sense of solitude and introspection that would define Hopper’s style, offering viewers a glimpse into the depth of his perspective on isolation.

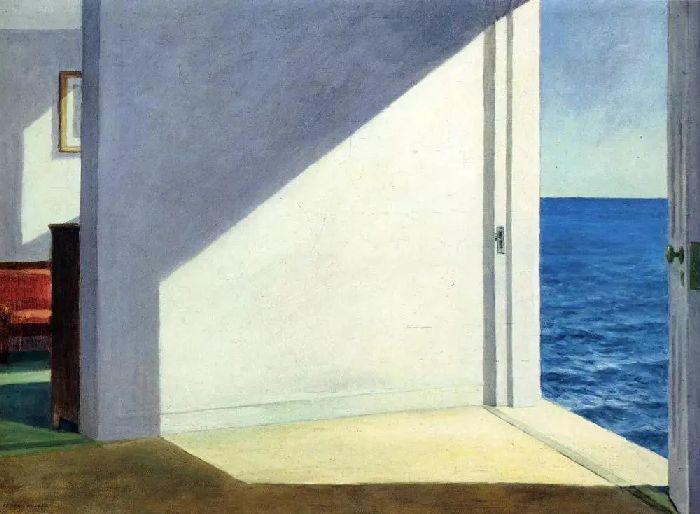

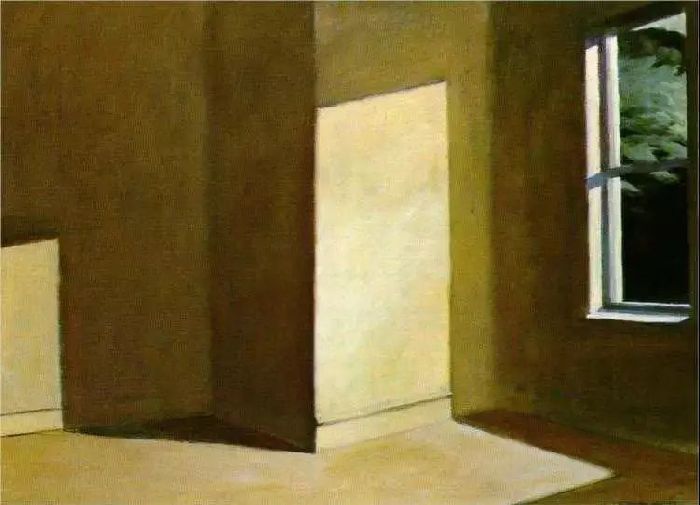

Hopper’s fascination with light began in his childhood. He once remarked on the joy he felt when sunlight illuminated the upper parts of a building differently from the lower sections—a fascination that profoundly influenced his later works like Rooms by the Sea (1951) and Sun in an Empty Room (1963). His mastery in manipulating light, both natural and artificial, allowed him to evoke complex emotions, from the eerie stillness of fluorescent-lit cafes to the unnerving clarity of a sun-drenched room.

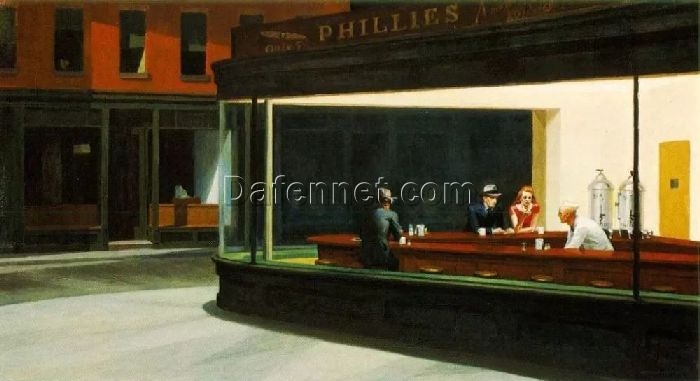

While Hopper initially struggled for recognition, selling his first painting, Sailing (1911), was a turning point. His breakthrough came with House by the Railroad (1925), a melancholic portrayal of isolation set against an urban backdrop, marking the beginning of his exploration into desolate cityscapes. His magnum opus, Nighthawks (1942), captures the quintessential Hopperian theme of urban loneliness—four silent figures in a brightly lit diner, each lost in their own world despite their physical proximity.

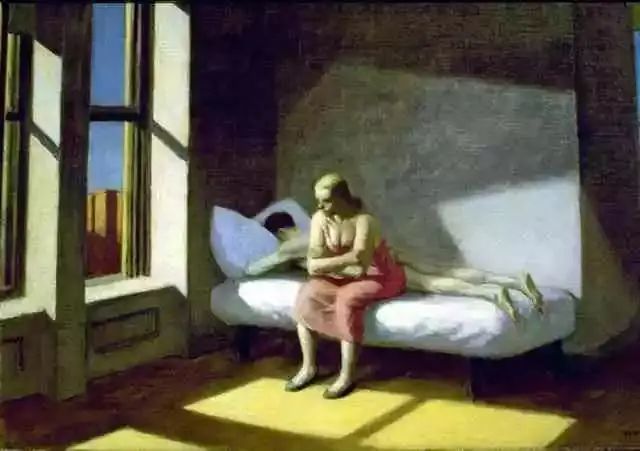

Hopper’s genius lies in his ability to use space, composition, and light to evoke a profound sense of separation. His works, like Summer in the City (1950), Hotel Lobby (1943), and Office in a Small City (1953), transport viewers to a realm where silence speaks volumes. Whether depicting figures in a café or individuals in starkly lit rooms, Hopper creates an ambiguous narrative that invites us to imagine the emotions and stories behind his characters’ vacant stares and isolated postures.

Through his art, Hopper transforms the abstract concept of loneliness into a tangible experience. His unique ability to capture the melancholy of modern life resonates deeply, making him an unparalleled interpreter of urban solitude. His works remind us that even amidst the bustle of city life, the human condition is often marked by quiet introspection and a yearning for connection.